Some of these microfilm rolls were later deposited in the national archives. (This compact form was more economic and durable for delivering the technical documentation to all the service facilities, especially to those located overseas).

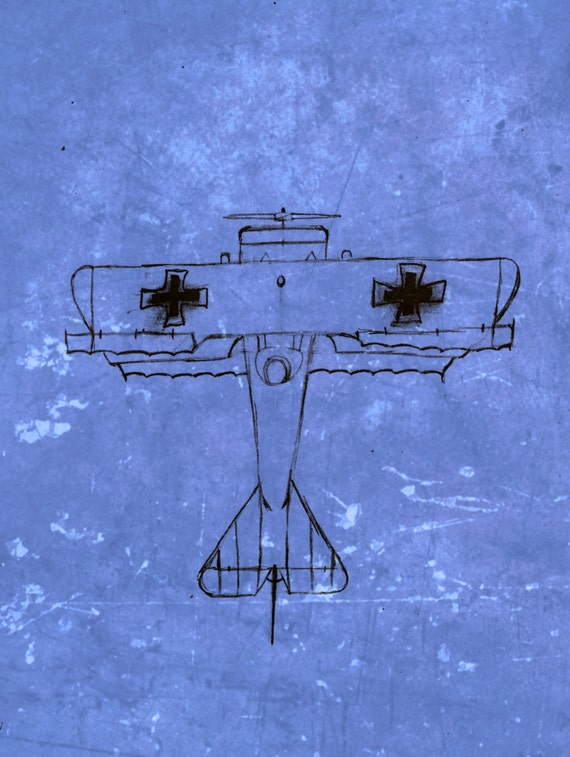

In the WWII period they started to reproduce these drawings on microfilms. Because of this factor, coupled with the usual wear and tear, the aircraft manufacturer had to continuously provide new replacements of the workshop drawings for the production and service purposes. Unfortunately, the contrast of the blueprints and diazoprints gradually faded after a few months of use (they are sensitive to light). The diazoprint copies were preferred, because of their bluish lines on white (more-or-less) background (as in Figure 97‑2): Figure 97-2 A diazoprint copy of the P-36 drawing The older blueprint method was passing out in the 1930s, because it produced white lines on the Prussian Blue background (as in Figure 97‑1).

For the “everyday” use, the factory made cheap (and volatile!) workshop copies of these drawings, using the old blueprint or the newer diazoprint methods.īoth of these copying methods produced 1:1 duplicates of the original drawings. (If there was not enough time, it could be even a pencil sketch). Such a “total destruction” could occur, because in the “pre-computer” era there was just a single master drawing of each part, made (if there was enough time) in black ink on the tracing paper. The original technical documentation of an aircraft usually becomes a bunch of useless, unreadable paper rolls that disappear in trash bins. After a few decades most of these companies are sold, while the less successful ones are out of the business. When the production of an aircraft is definitely closed, and it quits the service, its blueprints are packed into manufacturer’s archives. Figure 97-1 This copy of the P-47 drawing was made using the old blueprint method And even those, who saw these drawings, often did not know what they are seeing). (Everybody wished to have this ultimate resource, but only few saw it. During the long hours of studying the photos and trying to figure out the precise shape of this plane I often wished to have its source blueprints! For many years the access to the original documentation was “the Holy Grail” of the advanced modelers. You can see this in my work on the SBD Dauntless.

Recreating geometry of a historical aircraft is usually a painstaking, iterative process.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)